Awesome Project: BlackSpace Urbanist Collective

Published September 01, 2020

The idea for the BlackSpace Urbanist Collective first emerged in 2015 at the Black in Design Conference at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. “The conference was about Black urbanism and looking at it from the perspective of architects, artists, urban planners, and other designers,” Emma said. It’s a perspective that was, and still is, often overlooked in the mainstream urbanist world despite a long history of racist systems and actions, from the urban renewal and highway projects that devastated Black communities in the 20th century to the contemporary processes of development and gentrification. Naturally, it struck a chord. “We wanted to continue having the conversation after the conference, so we started having brunch,” Emma said.

In its first few years of existence, those brunches were an informal communal extension of the conference for the Black designers and planners who craved it. “When I look back,” Emma said, “a lot of that time was about unlearning and sort of unpacking a lot of the things that were happening in our professions and the toxicity that we inherited through our institutional jobs, our education.” Having been educated in, and often working in, predominantly white places, the opportunity to do that work was significant for BlackSpace’s members.

But they were also doing new learning together, exploring what a new school of urbanist thought might look like. “[Our] schools of thought came from the neighborhoods that raised us, the people that raised us,” Kenyatta McLean, another co-founder, said. “And also all of the Black practitioners and scholars that we in some way found, because it for sure had to be a scavenger hunt because they don’t put us in the mainstream curriculum of architecture and urban planning and design. So we were articulating different Black practices of urbanism.”

As they developed a new school of thought and built trust amongst themselves within the collective, they decided together that they were interested in putting it to practice. What would it look like for this collective, made up of urbanists of all kinds, to work across disciplines and do so rooted in their values? So they tried it.

Of the numerous projects that BlackSpace has undertaken, one that might typify their work best is their work in Brownsville, Brooklyn, where they were invited to develop a project to preserve Brownsville’s history and heritage.

A traditional heritage conservation project might center an architecturally significant building. But BlackSpace had an unorthodox project from the very beginning. For one, they defined heritage conservation much more broadly than just physical buildings, and included “culturally significant markers, both non-physical and physical.”

Then there’s the fact BlackSpace started their conservation project without an end goal even in mind. Yes, they knew that they wanted to do a project that conserved and honored the Black heritage of Brownsville. But they didn’t know at the outset what that would look like.

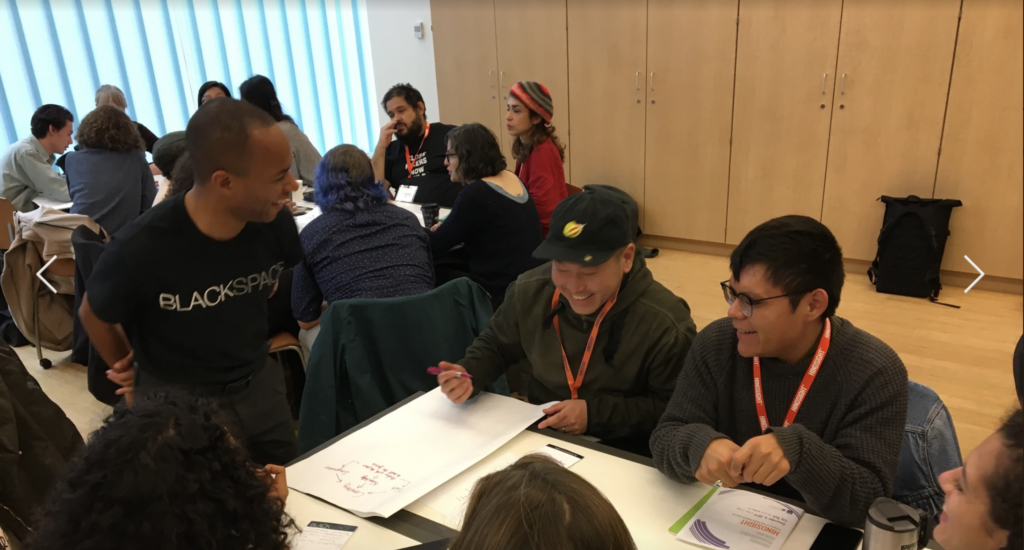

“One of the principal tenets that came out of those early [BlackSpace] meetings as a deeply held value was co-creation, understood with no qualifications, the way that it often is in mainstream planning,” Kenyatta said. “We didn’t know [the end goal] because we needed to spend time with folks in the neighborhood in a deeper way and a focused way to figure out what would be interesting, and what would be helpful to the already existing work that we know is there.”

Naturally, they began by listening.

BlackSpace listened to traditional stakeholders, but they also listened to everyday neighbors and their stories about the neighborhood’s history. As they talked, they mapped pieces of that history on a map, and they started to synthesize what they were hearing into a series of values that neighbors were lifting up as particularly important, like the need for intergenerational storytelling. The conversations were rich, and it was clear they were tapping into something.

But it soon became clear that they needed to pause. The BlackSpace team had collected a lot of stories, but they knew that Brownsville wasn’t a monolith and that there were many, many stories to tell. They also knew they couldn’t possibly capture them all. So they thought about the people who were already preserving and celebrating the neighborhood’s heritage, whether they knew it or not: cultural producers like writers, musicians, muralists, and others. They asked, how might these producers continue to tell those stories and conserve Brownsville’s rich heritage? Then, BlackSpace listened some more.

They listened for what it would look like for them to conserve history and heritage, and they listened for what the future could look like. “What sort of emerged were these kind of magic moments where through the value of BlackSpace’s convening and facilitation, cultural producers started riffing with each other: ‘Oh, if I run an adult writers group, and you have a mural nonprofit, and you run public events for the BID, what does it look like if our writer’s group tells stories to the upcoming street festival goers, in front of the murals on the block!,’” Emma said. “That idea became a pop-up neighborhood storytelling tour focused on intergenerational storytelling. It wasn’t, let’s build a building tomorrow, right? It was like, this is what we can sustainably work towards, together ”

The project ultimately culminated in an event, a “Heritage Happening” as BlackSpace called it, where neighbors could interact with and engage with some of that history and heritage. But new connections and partnerships also emerged far beyond it. They even co-produced an anthology of writing from a neighborhood writing group, Power in the Pen — who are also now raising funds on ioby; beyond the realm of traditional urbanism and heritage conservation, but for BlackSpace, it was an obvious move given the value they placed on heritage that extends beyond simply significant buildings.

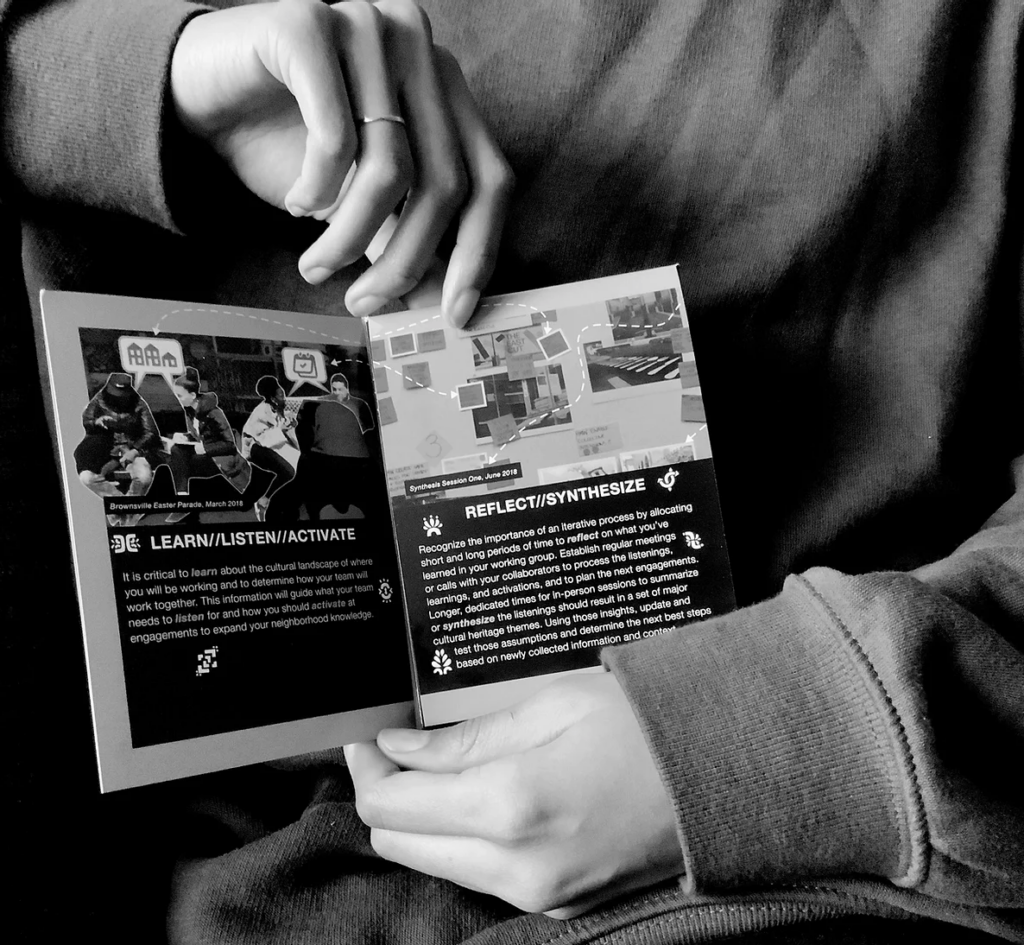

Their work in Brownsville, in partnership with the Brownsville Heritage House and others, was just one of a series of engagements BlackSpace has had across the city and the country, but what emerged from it was a template for how they wanted to do work. The collective learned a lot working in Brownsville, and they turned those learnings into a manifesto; a statement of principles and ideals to which their work—and, they hope, the work of other urbanists—would aspire toward. It lifted up things like Black joy, moving at the speed of trust, deep listening, and other values long at the center of activist and movement work, but not always central to the practice of urbanism. Their manifesto was a corrective to the mainstream, and it honored the collective’s own lived experiences.

Drawing from the manifesto and from their work in Brownsville, they later produced a playbook—a kind of guide for others looking to emulate this new model they developed which centered community, and which centered co-creation. The playbook itself was co-designed with Made in Brownsville, now the Youth Design Center, a nonprofit in the neighborhood. Two of BlackSpace’s members also taught university-level architecture courses that centered the Manifesto so the tools are integrated into the design curriculum, and take these methods into their various jobs as practitioners.

Taken together, what emerges from BlackSpace’s body of work is really a pathway to a new future. It’s a way of thinking and a methodology to, in BlackSpace’s words, demand a present and future where Black people, spaces, and culture matter and thrive. In other words, to ensure that Black lives matter.

To continue to grow their vision and expand their footprint—while founded in New York, they host affiliates in Chicago and Oklahoma as well and are planning to launch more where there’s interest—BlackSpace knew they’d need funding.

Grants have been a place they’ve turned to for funding, but they’ve also leaned on crowdfunding with ioby—for both fiscal sponsorship as a presently unincorporated group and to raise funds. “Last year we did our first [ioby crowdfunding campaign] during Black History Month as kind of our first venture into not only engaging our network in that way, but also checking in on how folks are trusting our vision,” Kenyatta said. “I think crowdfunding in a way is that. You’re able to check in with a network of advisors to say, “Oh yeah, we’re behind this. This makes sense.”

What they received was a resounding message of support. The campaign exceeded their original goal, raising just over $7,500 to cover some of the basics of operating, like website services and programming.

It was a strong start, but coming into this year the collective knew that they would need more funding than they’d ever raised before in order to build the internal infrastructure they would need to really grow. So they launched what they called their Chrysalis goals—a series of strategic goals that, if met, would put them in a strong place to continue their work well into the future. A key component of that plan was raising significant financial resources in order to have the sure footing for things like a full-time staff, multi-year engagements, and more. So they started an ioby campaign and, over the course of a campaign that stretched out over roughly six months, raised over $135,000.

It was one of the largest projects to ever crowdfund with ioby and it succeeded, they said, because of their strong network. “Fundraising for us is a community endeavor,” Emma said. “One of the ways that BlackSpace functions is like, whoever’s in Kenyatta’s network is in my network and whoever is in my network is in Kenyatta’s network. And so it creates this very wide net because we operate in a collective fashion. That network, you can just imagine, it just exponentially multiplies.” They reached over 500 donors, spurred to give largely through the power of word of mouth.

Another reason for their success was because they used their campaign as a kind of hub for gifts from all kinds of places. BlackSpace’s board members made their annual contributions through the campaign, and with ioby as their fiscal sponsor, they also received grants from foundations through their campaign. “It really was a full effort,” Emma said. “All those things sort of work together to instill trust so that more people would understand that we were a thing…and people trust us. Which is important in crowdfunding. And I think that all of the gifts together inspired more people perhaps than we’ve ever seen before support this work.”

They still have a number of other Chrysalis goals to achieve, including more funds that need to be raised, but there’s strong momentum behind them.

“I think as a part of Black Lives Matter and the importance of the defund movement, there is this importance in recognizing that not only should we be contributing to the bail funds, the mutual aid funds, and [working] to a point of defunding all these institutions that have been harming Black communities,” Kenyatta said, “We also have to decide to reimagine and manifest the future. And that’s the other side of the defund movement that’s important to recognize. Where do we invest? The idea is that we dont leave communities without any type of resources. And so I think we see ourselves as an idea or a collective that folks can invest in, and that knows that we want to continue to co-design those community-led projects that should be invested in and amplified because they are what is going to allow us to continue to make the world where Black lives matter.”

BlackSpace is still crowdfunding on ioby to continue to support their mission—check out their campaign!

Have your own idea for a project to strengthen your community? We want to help! Share your idea with us, and you’ll get one-on-one coaching and support, fiscal sponsorship, and more!